Weekly Outlook

What will the world lose on Victory Day?

In Western Europe, May 8th, the day that the Allies accepted Germany’s unconditional surrender in 1945, is observed as Victory in Europe Day or VE Day. In Russia and some other Soviet countries it’s May 9th, Victory Day. In most countries nowadays it passes without much notice but in Russia it’s a day for military parades and solemn remembrances to commemorate the 27mn Russians killed in the war.

As a recent article in The Atlantic reminds us, it’s also a day for speeches. Putin’s speech is likely to provide a clue about what he plans to do with his “special military operation” in Ukraine: bring it to an end or extend it to a larger war.

Russia-watchers are concerned that Putin will be keen to help his military avenge the humiliation of its abysmal performance in what was supposed to be a three-day war. British Defense Minister Ben Wallace has expressed the concern that Putin will use May 9 to press for the mass mobilization of the Russian people. This would imply not only an expansion of the war against Ukraine but also an escalation against the US and NATO.

But how much more capacity the Russians can bring to the war is unclear. If requires a large conscription effort, it will take months or even years before these new troops would be ready for combat. In the meantime, mass conscription risks angering a Russian public that has until now been—from a safe distance—largely supportive of the war. Similarly, the Russian defense industry, crippled by export restrictions, can’t quickly solve Moscow’s equipment problems and produce more of what are poorly designed tanks and defective missiles anyway.

Still, Putin might call for a final push to overwhelm Ukraine. He might see doubling down as a realistic option. This could impose some unity within the Kremlin and help to silence the average Russian who is thinking of protesting. The Russian military too might welcome an even more militarized nation.

The more worrisome possibility is that Putin decides to declare NATO the true source of Russia’s military problems and plunge Russia into World War III. Faced with defeat, he might decide against “peace with honor” like Nixon did in Vietnam and instead gamble the existence of Russia itself in an expanded war, betting that NATO will make peace before the Kremlin is left with no recourse but to cross the nuclear threshold. That would be The Mother of All “risk-off” episodes. Stocks would probably plunge and USD surge. Bonds might even make a comeback.

Meanwhile, the EU tries to strike back, but it’s hard to get 27 countries to agree on anything. The European Commission (EC) proposed phasing out all supplies of crude or refined Russian oil in an “orderly fashion,” according to the FT. The FT also said the commission is proposing to bar European ships from transporting Russian oil and products to any part of the world and to prevent European insurers from insuring its transportation. The latter would be an especially effective move as 95% of the world’s tanker liability cover is arranged through an organization that follows European law. These moves would make it more difficult for other countries that are not observing the embargo, such as India and China, to circumvent it.

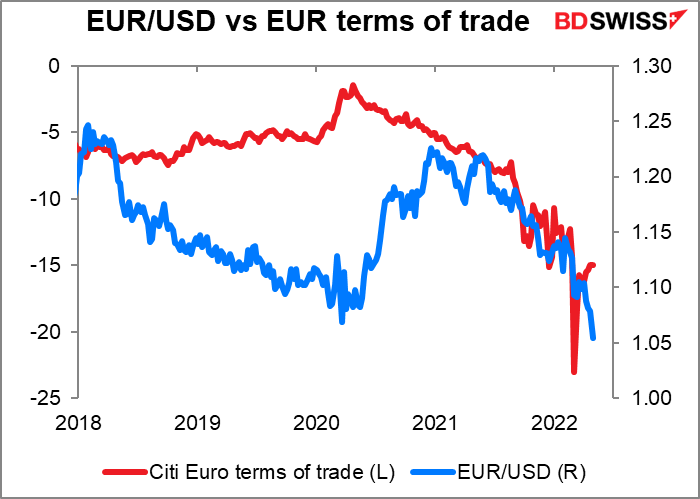

Economists at Barclays estimate that an embargo of all Russian energy imports could reduce euro area GDP growth by 1.3%, or as much as 5% if rationing is imposed. They estimate that since the Eurozone imports its natural gas and crude oil requirements, a 200% shock to European natural gas prices and a 40% shock to crude oil prices would result in a 4% deterioration in the Eurozone’s terms of trade.

While terms of trade haven’t always been a major factor moving the euro, for the last year or two the two seem to be moving in tandem (I hesitate to argue cause & effect). It would seem likely that if the terms of trade deteriorate further, the euro is likely to weaken further too.

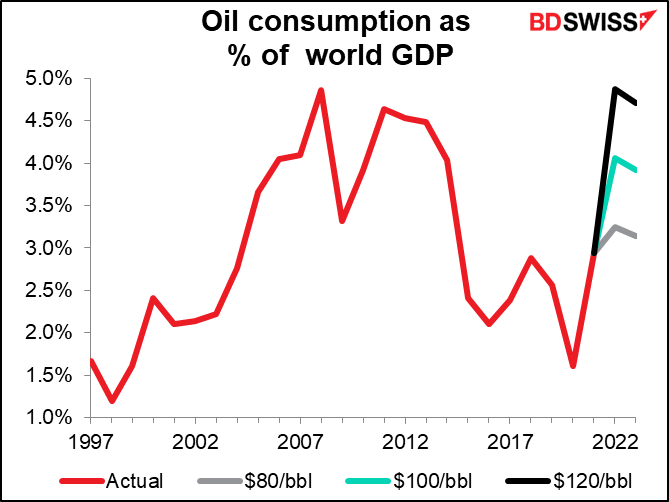

At the same time, a further increase in the price of oil risks sending the world back into recession. When we look at world oil consumption as a percent of world GDP, we can see that if the oil price reaches $120 a barrel, then oil will be consuming as much of the world’s output as it did shortly before the Global Financial Crisis. That’s not a healthy place to be, especially as central banks all over the world embark on tightening cycles and many governments try to reduce their budget deficits.

The coming week: US inflation, UK short-term indicators

The second week of the month is usually a quiet one for indicators and this month even more than usual. The main features will be several measures of US inflation and UK short-term indicator day on Friday.

In the US we get the consumer price index (CPI) on Wednesday, the producer price index (PPI) on Thursday, and import prices on Friday.

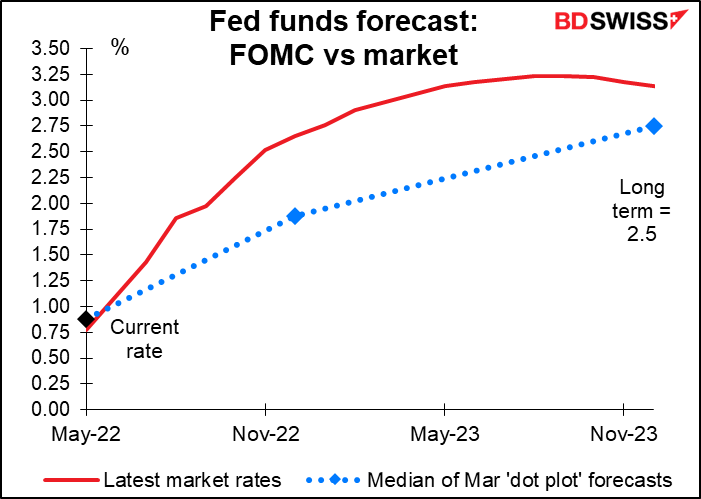

Before we look at the data, we have to ask: does it matter anymore? The Fed is on a tightening path, they’ve made it very clear how rapidly they’re going to tighten. It would take a big change in the trajectory of inflation to change their plans, either to get them to accelerate or to get them to back down.

Yet we have to be on the lookout for such an inflection point. Right now the market is still pricing in considerably more tightening than the Fed itself is assuming (although their forecasts are a little out of date now). The inflation data will tell us whether the market dials down its expectations to be more in line with what the Committee is forecasting or whether the Committee ultimately caves in to market expectations.

Next week’s data suggests that Fed Chair Powell’s cautious optimism may be warranted and that the Fed needn’t accelerate the pace of tightening.

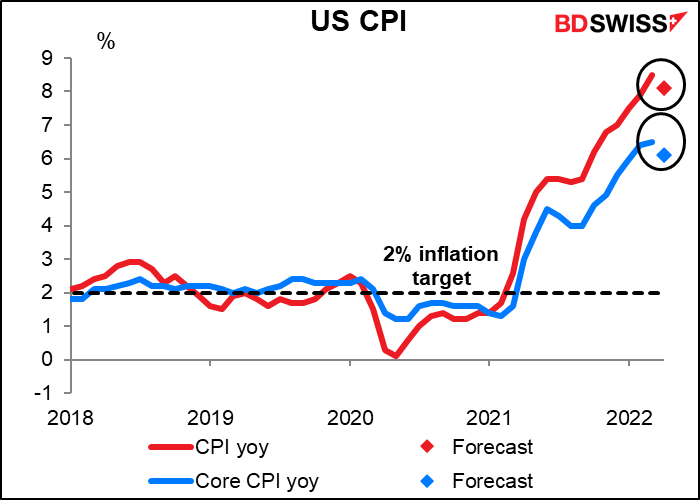

The CPI is forecast to fall a bit. Still remain far far above target, but at least on this forecast it may have peaked (as far as we know).

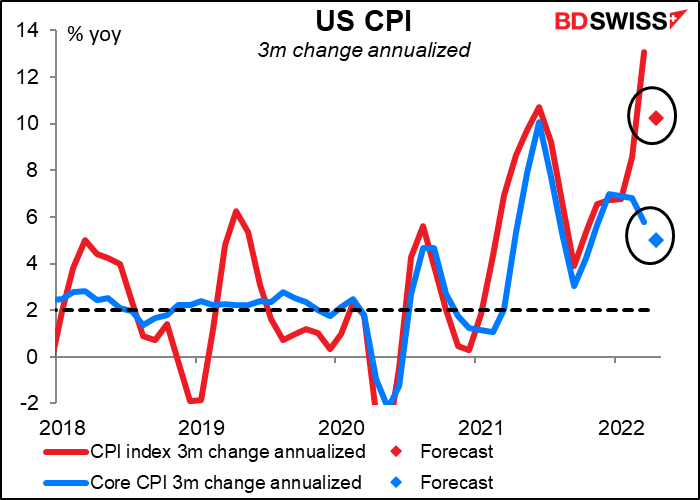

It’s the same when we look at the predicted 3-month change annualized. Still too high, but at least it’s not higher. This expected slowdown in inflation may confirm the Fed’s more tempered view and help stock markets to recover – while weakening the dollar.

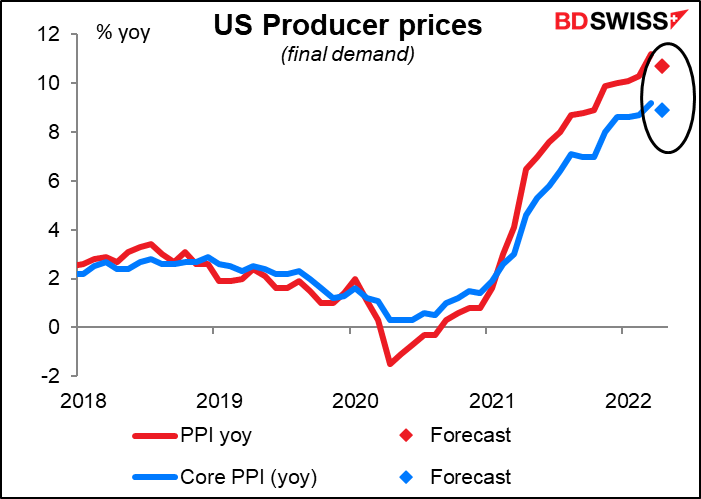

Ditto for the producer price index (PPI), where both the headline and core measures are expected to slow. Same for the annualized rate of change of the monthly figures.

No forecasts yet for the yoy rate of change in import prices, but the mom changes are expected to drop considerably.

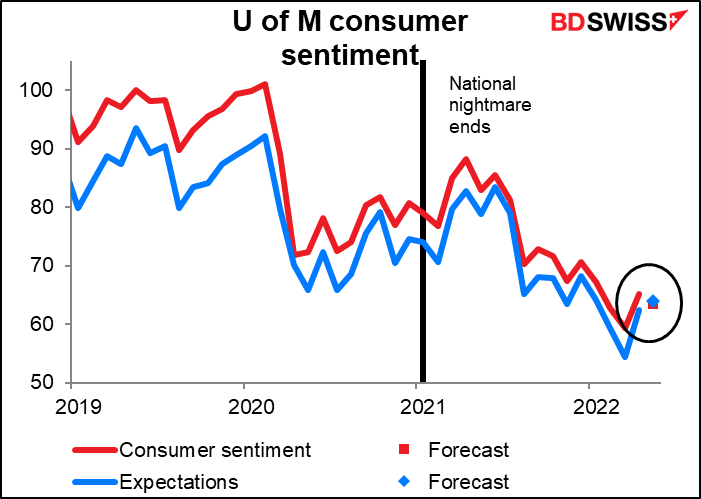

Meanwhile, the University of Michigan consumer sentiment index is expected to decline further. This indicator has shown notably worse sentiment than the Conference Board version, probably because this one focuses more on one’s personal finances, which have been hit by inflation and the plummeting stock market. The Conference Board survey on the other hand asks more about general macroeconomics, especially the labor market, which is booming.

Furthermore, as my fellow pundit Barbara Rockefeller points out, the U of M survey is based on a mere 500 phone calls. Those surveyed are asked 50 questions. Who has the patience for that? Retired people. They may be older and wiser, but they may also have strong biases, too.

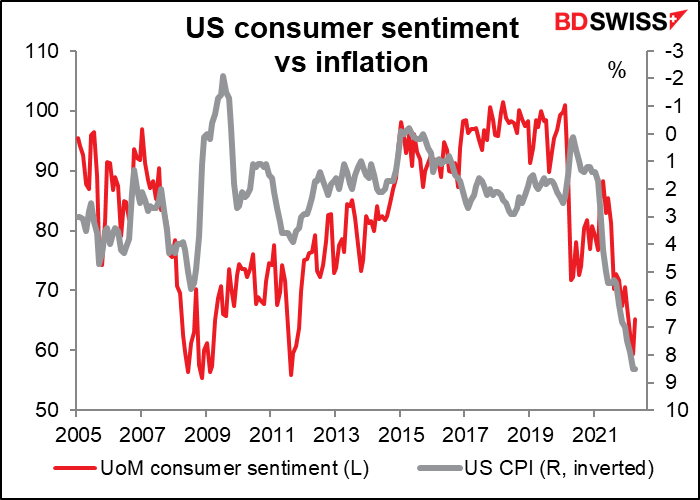

As you can see, the index tends to follow inflation: inflation up, sentiment down. What does this really tell us about the future economic activity of American consumers? Not much, really. But many people believe it does and watch it nonetheless and so affects the market.

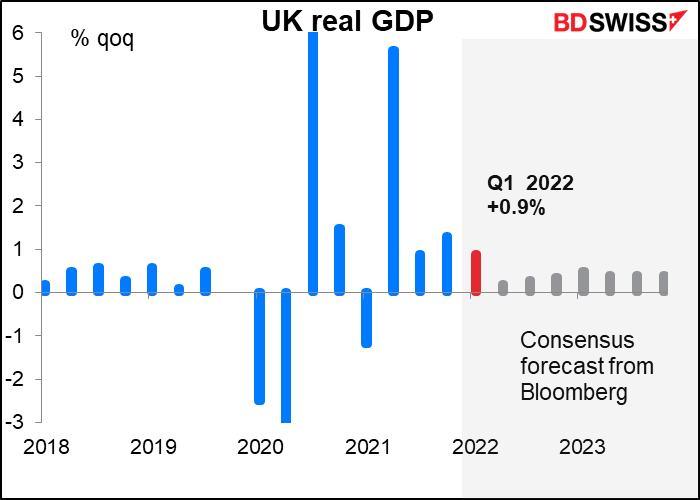

Thursday is “UK short-term indicator day,” when they announce several indicators that have a bearing on short-term developments in the economy, namely: GDP, industrial & manufacturing production, and trade. Attention this time will no doubt focus on the Q1 GDP figures.

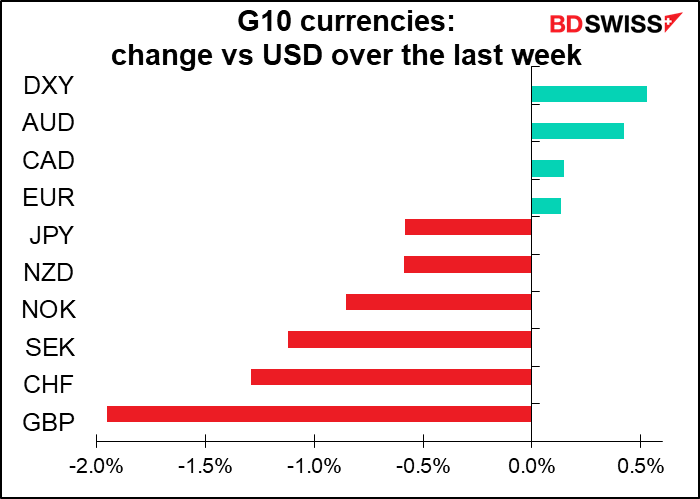

The +0.9% qoq increase is in line with the Bank of England’s estimate in yesterday’s May Monetary Policy Review and so would not have any implications for policy. A deviation might though, especially a deviation on the downside. A miss to the forecast would only increase the concern of those members of the Monetary Policy Committee who are worried about plunging the economy into recession. The market would probably react by removing even more tightening from the forecasts, which would be negative for GBP. A beat however wouldn’t prove anything at this point because the outlook is still grim. Thus I think we have an asymmetrical downside risk from the UK GDP figures.

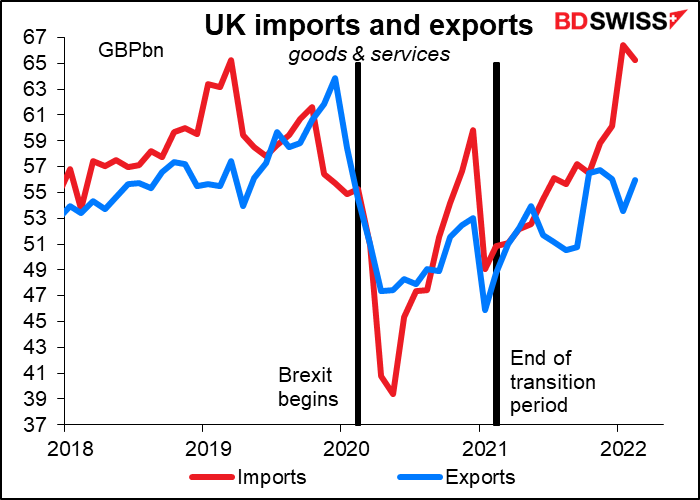

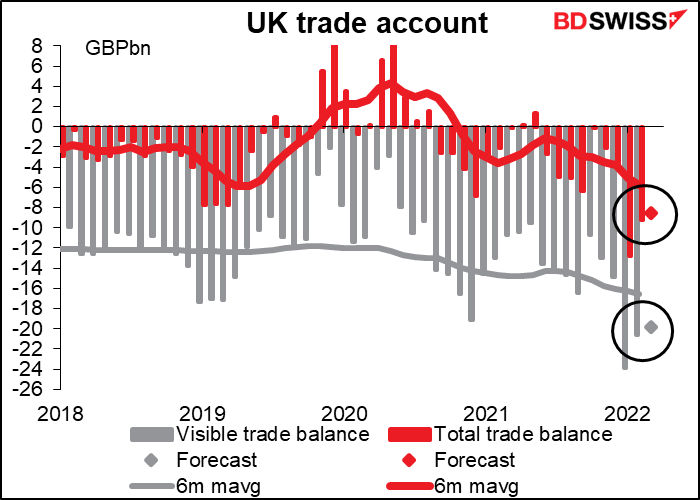

The trade deficit is expected to narrow imperceptibly.

That may be because imports are turning down a bit. It certainly doesn’t seem to be due to any surge in exports. We are all waiting for the Brexit bonanza when the UK, liberated from the constraints of unreasonable EU regulations, is finally able to enter into much more beneficial trading pacts with the other nations of the world, such as Nauru, Tuvalu, Andorra, etc.